Set to air March 15 on the Paramount Network after its SXSW world premiere, “I Am Richard Pryor” is a largely satisfying if thoroughly conventional portrait of the immensely gifted and deeply troubled entertainer whose richly deserved reputation as a comic genius stems at least partially from his frequent and fearless willingness to make himself the target of his take-no-prisoners humor.

Director Jesse James Miller has entwined film clips, archival material and talking-heads interviews to fashion what occasionally feels like an officially sanctioned biography — an impression only reinforced by the billing of Jennifer Lee Pryor, the subject’s widow and a recurrent interviewee in the film, as an executive producer. Still, the story that emerges is undeniably fascinating, and may prove especially intriguing for viewers who have only recently discovered the late legend through his scripted features and comedy-concert films.

Even longtime fans of Pryor might be surprised by those sections of the documentary that illustrate highlights of his early career, during a time when the only way a black comic could hope to achieve mainstream success was to come across as safe and unthreatening as Bill Cosby did. (Miller is savvy enough to just place that factoid squarely on the table without any side orders of shade or snark.) At one point, we see a snippet from a 1966 episode of “Kraft Summer Music Hall” in which Pryor appears alongside a well-groomed George Carlin and a squeaky-clean John Davidson — and all three men look like they’re ready to join an Up With People singalong.

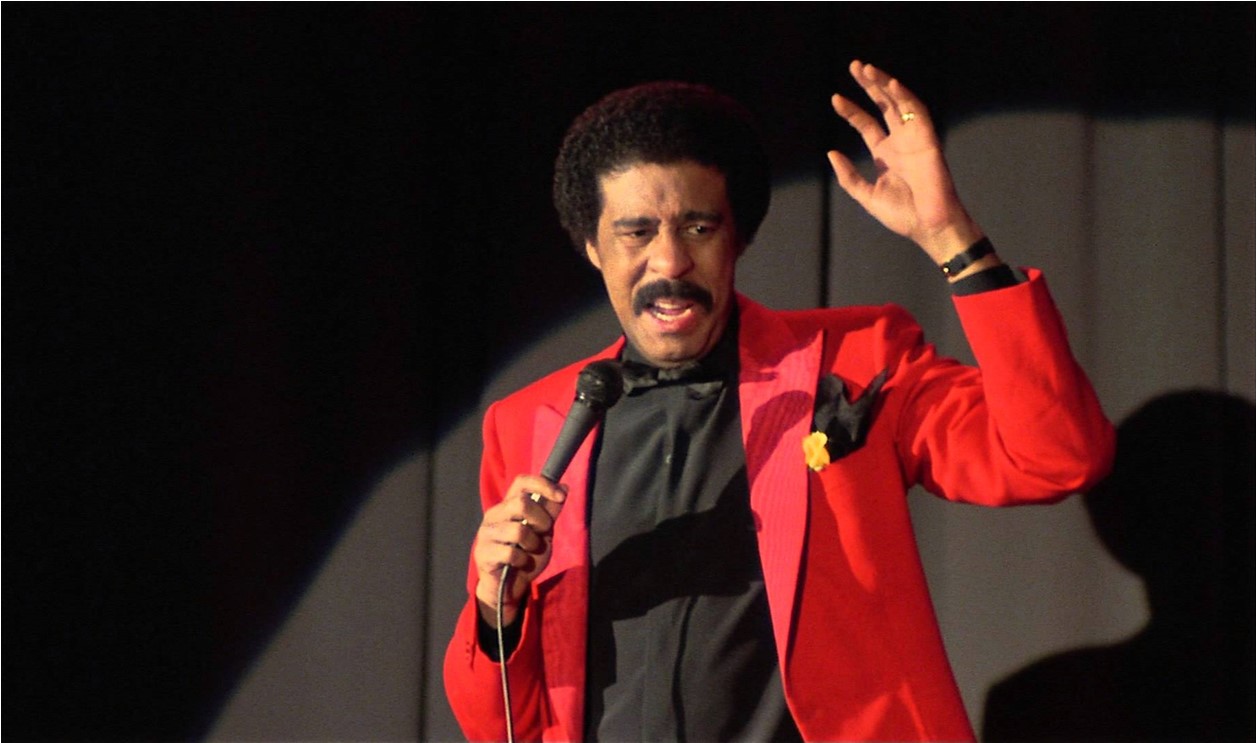

Pryor couldn’t play that game very long, however. After literally walking away from a high-paying Las Vegas gig (which, the documentary pointedly observes, called for him to perform for mostly Caucasian audiences), he blazed a path to stardom on his own terms with much edgier, more personal, and unapologetically foul-mouthed stand-up material. Tiffany Haddish, a contemporary comic performer who credits Pryor as an influence, sounds at once admiring and astonished as she marvels at how, as early as the 1970s, Pryor was offering savagely satirical commentary on, among other issues, police shootings of African-American men.

Miller’s narrative proceeds on parallel tracks that often intersect, showing how Pryor’s vertiginous mood swings and ever-increasing reliance on drugs failed to impede — for a while, at least — his string of successes as a live performer, on comedy records (his 1975 Grammy Award-winning “That Nigger’s Crazy” is duly noted as a groundbreaking career highlight) and, of course, in movies.

There’s a case to be made that “I Am Richard Pryor” could have benefitted from a wider range of scenes from Pryor’s cinematic oeuvre. It would have been amusing, and revealing, to see a very young Pryor — cast as a cop! — making his movie debut, and holding his own opposite Sid Caesar, in William Castle’s “The Busy Body” (1967). And it might have been downright gobsmacking to see Pryor and Bill Cosby actually together at long last in the 1978 film of Neil Simon’s “California Suite.”

Seeing Pryor at his most hilarious makes it all the more painful to follow “I Am Richard Pryor” as the documentary charts his decline and fall. Naturally, the film pays an appropriate amount of attention to the night in 1980 when Pryor nearly burned himself to death while freebasing. But long before that, Miller makes it clear, early and often, that Pryor was psychologically scarred by his harsh childhood in Peoria, Ill. His mother was a prostitute, his father was a pimp and his grandmother was a madam — facts he carefully scrubbed from his biography during his salad days in showbiz, but never, ever forgot.

Jennifer Lee Pryor, along with other intimates and admirers, describe with equal measures of affection and clear-eyed explicitness a brilliant but undisciplined artist who could never fully control his demons. And while his rages sometimes were justified — such as when he battled nervous network censors of his short-lived NBC variety show — he made impossible demands on the people who cared about him most, and caused collateral damage with his self-destructive impulses. “I Am Richard Pryor” celebrates its subject. But, to its credit, it stops short of entirely excusing him.