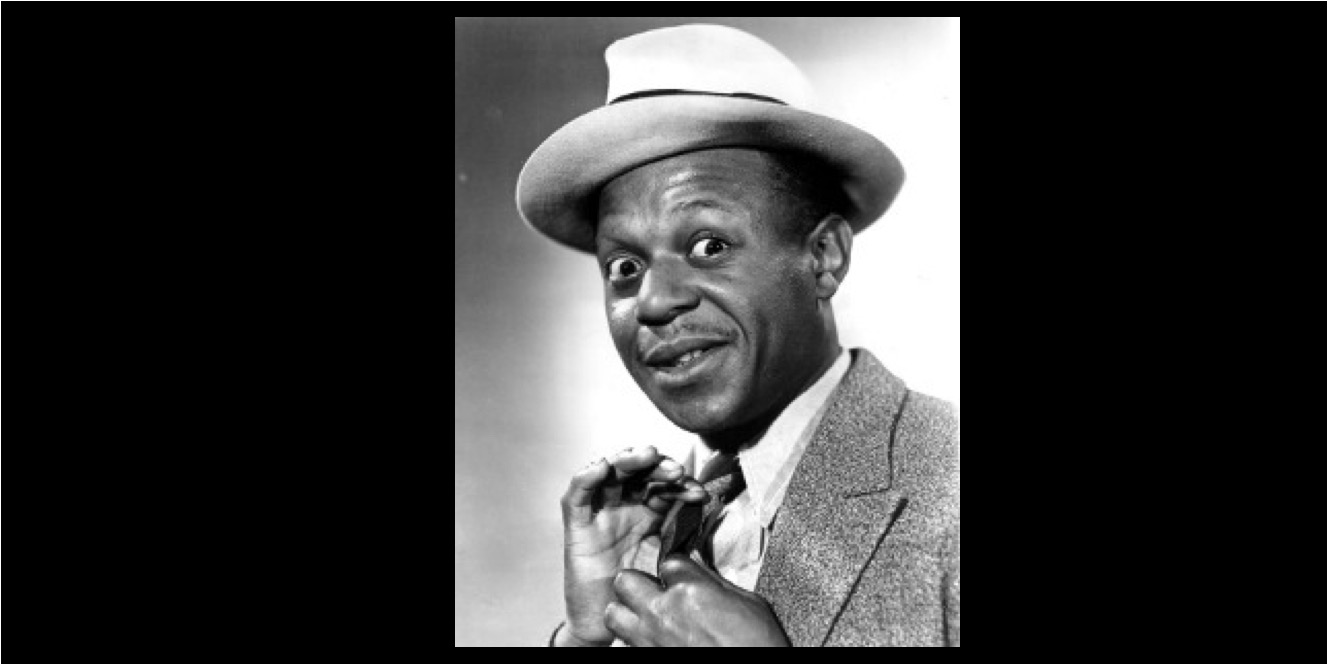

On this day in comedy on February 28, 1977 Comedian, Actor, Edmund Lincoln Anderson (best known as “Rochester”) died.

With an instantly recognizable raspy voice due to rupturing his vocal cords yelling as a paperboy in his youth, Eddie Anderson was the first black man to be a regular cast member on radio. He worked a number of odd jobs after leaving school at age 14 to help out the family, but the lure of back stages kept tugging at him. He’d clown around with his brother, Cornelius which led to performing as a dancer in an all-black revue on the vaudeville circuit. He got picked up and appeared in “Struttin Along” in 1923 and later “Steppin High” with Cornelius in 1924. He added comedy to his act in 1926 and then he met comedy legend, Jack Benny, the man who would change his life.

Anderson met Jack Benny by chance. They exchanged greetings, shook hands and went their separate ways. Little did Anderson imagine that he shook the hand of the man who he’d spend most of his career. When they met again Anderson was auditioning for the part of a Pullman porter in a Benny radio episode that took place on an actual train moving across country. He got the part when the shoeshine man, Oscar, at Paramount, who Benny had in mind for the part involved his agent (yes, the shoeshine guy had an agent) who asked for $300. Benny thought this was high for 1937 and gave the role to Anderson, who was doing comedy on Central Avenue in Los Angeles. Anderson was so memorable that he was called back 5 weeks later to play a waiter and join the cast in a Jell-O commercial. Letters poured in and he was called in again a few weeks after that to play a guy in a financial dispute with Benny. More letters flooded the studio and Benny decided to make Anderson a cast regular. He’d be Rochester, the valet who would talk trash to his boss. That initial back talk turned into a lengthy, lucrative career.

By 1940 Anderson was the most popular character on “The Jack Benny Show” next to Benny. He was elected Mayor of Central Avenue, an honor which carried the right to speak on issues involving blacks in that area. Anderson’s platform was getting blacks to become aviators. After he received press pushing this agenda, President Franklin Roosevelt made the same plea. Build a strong national air force.

Racial lessons were learned due to Rochester. After World War II people were more sensitive to racial bigotry. A script that had been used prior to the war was reused 7 years later with disastrous results. Listeners called and wrote in how stereotypes about Negroes was unacceptable. Benny demanded that his writers remove all racial negativity from all future scripts and went on radio to compel his audience to reject racism and endorse brotherhood of the races. Nevertheless, racism plagued the times. Anderson could not tour with the cast to entertain the troops because as a black man he would require separate living quarters. (Yeah, right). Yet when his name was mentioned the soldiers applauded more for him than any cast member present. Stateside Benny would have to threaten to leave a hotel if they would not let Anderson stay there as well and sometimes that threat was a promise like the time in New York when the entire crew of 44 people checked out with Anderson.

Despite these indignities Eddie Anderson was the highest paid black actor until the 1950s. He owned a sprawling estate in West Adams area of Los Angeles renamed “Rochester Circle” as well as races horses and a boxer, not to mention various businesses. In 1951 when “The Jack Benny Show” went to television Anderson went with it. He also did guest starring spots as Rochester on “The Milton Berle Show” (1953) and “Bachelor Father” (1962). “The Jack Benny Show” went off the air in 1965.

The Benny association was a major boost, but Anderson’s career wasn’t all Jack Benny. Anderson was in the Benny films, “Man About Town” and “Buck Benny Rides Again”, but he also co-starred with Ethel Waters and Lena Horne in the classic, “Cabin in the Sky”. He appeared in the comedy film classic, “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” (his last screen performance). All totaled Anderson appeared in over 60 motion pictures, including “Gone with the Wind” and “Jezebel”. Regardless, there was still ignorance to tolerate. One of his films, “Brewster’s Millions’ (1945) was banned from theaters in the South because “it presents too much social equality and racial mixture.”

A complete entertainer, Eddie Anderson touched all mediums. He did game shows, provided voices for cartoons, performed comedy in night clubs and appeared on Broadway. In 1975 Anderson was elected to the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. On this day in 1977 he died of heart disease in Los Angeles at the age of 71 and posthumously inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 2001.