In the last 30 years, has any movie form been debased and degraded more than the horror film? Most fans of the genre wouldn’t agree, but it always astounds me the extent to which mainstream horror movies have become blood-soaked funhouse video-game rides full of lurching logic, driven by shocks and jolts and soundtrack gongs and the same old “Amityville”-meets-“Exorcist” devil-in-the-haunted-house tropes.

The first revelation of “Get Out,” Jordan Peele’s exquisitely creepy and fun African-American nightmare movie, is that while it does have its moments of extreme violence (your jaw will drop, your spine will shudder), it’s a classical piece of old-school moviemaking: a drama of pace and suspense and motifs and relationships and three-dimensional space and psychology. In telling the story of Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya), a black photographer in his mid-twenties who drives upstate with his white girlfriend, Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), to visit her parents, only to learn that he has walked into a slowly unfolding vortex of racial terror, Peele, who wrote and directed, evokes the spirit of Roman Polanski: the cinema of plausibly unsettling paranoia he created in “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Repulsion,” and “The Tenant.” That “Get Out” is also a primal racial satire made with a scandalous glee in no way detracts from — and only enhances — its analog mode of conspiratorial dread.

Another way to say this is that Jordan Peele, in having made an enthralling, deftly acted, impeccably shot, and subversively ambitious horror film for the princely sum of $4.5 million [insert cliché joke about the craft-services budget of XXXX here], and in proving that he can summon a blockbuster crowd for it — $30.5 million worth of tickets sold in one weekend to a racially diverse audience — has with a single February movie reminded us what the creative possibilities of commercial filmmaking really are. A studio executive, if he happened to be of the corrupt sort, might have watched the rushes of “Get Out” and said to Peele, “We need more violence in the second act” or “You’re taking too much time between beats.” But the whole suspenseful beauty of “Get Out” is that the film is willing to take its time to usher you into a queasy African-American version of the Twilight Zone. It’s Rod Serling meets James Baldwin, with a scalding touch of “Mandingo.”

The slyest thing about the movie, which Peter Debruge reviewed brilliantly here, is that it’s an equal-opportunity racial-burlesque creep-out. Our hero, Chris, already has his radar set on “approach this situation with extreme caution” when he drives off with Rose, whom he’s dated for five months, for a meet-the-parents weekend at the rustic estate of her wealthy liberal folks. Her mom, Missy (Catherine Keener), is a psychiatrist who specializes in hypnotherapy, and her dad, Dean (Bradley Whitford), is a bearded, horn-rimmed, smugly bourgeois neurosurgeon whose over-worship of Barack Obama and pointed use of phrases like “My man!” only serve to underscore how completely he sees black people as…a category. From the outset, we’re cued to see that these people are not what they seem, and part of the joke is that liberals, by definition, are not what they seem. The very fact that they “mean well” means that they’re the opposite of color-blind. “Get Out” starts off as a slashing satire of white people, a disarming projection of what even “enlightened” Caucasian culture looks like when the masks come off.

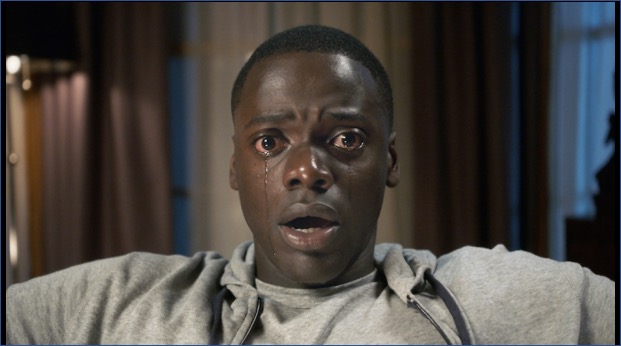

But the movie, in its sneaky way, is also a slashing satire of black identity and anxiety. Chris, the hero, is never a figure of mockery — the sensational British actor Danial Kaluuya makes him the film’s wary center of gravity, always holding his power in reserve, which means that much of his performance is a riveting series of reaction shots. He can’t believe the patronizing cluelessness of everything he has to play along with. (He cues us to see the inner eye rolls that he can’t display.)

Chris, though, has seen it all before. The newly disturbing thing to him are the other black people on hand: the servants at the Armitage home, who live in an ambiguous polite smiling daze, or the one black guest he meets at a garden party. They’re all wearing masks of their own. There’s a ticklish daring to the way “Get Out” calls up echoes of slavery to say that African-American culture, in 2017, includes a daily level of social brainwashing. When Chris discovers a box of photographs of Rose (the movie’s “All work and no play…” moment), it’s a racial-erotic joke: the fulfillment of every skeptical outcry ever voiced by an African-American woman as to why African-American men shouldn’t date Caucasians. And when Chris, strapped to a chair, is forced to watch a video on an old TV set, the fear factor isn’t just in seeing the white monsters he’s up against. It’s the terror that he’ll be coerced into slipping into an identity of subservience. A sunken space.

The tricky paradox of “Get Out,” and the movie’s outrageous triumph, is that it’s a horror film that lays waste to the liberal dream, blasting apart fantasies of a kinder, gentler, color-blind, “post-racial” America. Yet part of the film’s catharsis is that its very existence proves that we’re strong enough, as racially diverse moviegoers, to unite and giggle in fearful suspense at a vision that hits this luridly close to home. We may not — yet — be one nation under a groove, but we’re one nation under a megaplex roof. And we’re more than ready for a horror movie that uses the elixir of organic storytelling to bring us together by laying bare the ways that we remain scandalously apart.

By: Owen Gleiberman/Variety